During the research phase of the recent Mile Cross 100 project one of the little details we were hoping to find out was who were the first people to move into a Mile Cross home on the new estate, however, I wasn’t surprised to learn that we couldn’t figure out exactly who those very first tenants were. I mean, we had some names of people who were here in the beginning, but it was nigh-on impossible to pin down any one person or family that were given the very first set of keys here in Mile Cross, which was a bit of a shame. We knew that people started moving in to some of the first purpose-built Council-owned homes in around 1923, at around the same time, or not long after the new bridge at Mile Cross was opened in September of the same year. By using the Kelly’s Directories (Heritage Centre, top floor, Forum) of the time I did manage to build a fairly accurate map of which streets were inhabited, and in which years. For example, at the start of 1924 there were people already living at Bolingbroke Road, Chambers Road, Civic Gardens, Losinga Crescent, Marshall Road and Rye Avenue, but not all of those roads were yet fully inhabited, or indeed completed at this point. People were effectively moving into a building site, and this theme continued on for about seven years.

During a visit to the Norfolk records Office, an interesting document surfaced, discovered by one of our researchers and titled ‘Council Meeting – 19th December 1922. Notes for the Chairman of the Housing and Flood Prevention Committee about a collection of ‘wooden hutments’ that really caught my attention. Woah back… As I typed that, It suddenly dawned on me that I just put the word “interesting” in the same sentence as what is in reality, a really dull-sounding document. Welcome to dull men’s’ club! Anyway, this document caught my attention for a number of reasons, but mostly because it contained a reference to Mile Cross before the estate was built, and because it was referring to accommodation being built here. I’ll shed a little more light as I continue (being really dull – quiet, brain!).

The document was referring to a report submitted by the City Engineer, Arthur Collins which was talking about the cost effectiveness of building a collection of wooden ‘hutments’ at the Angel Estate, Mile Cross or Earlham, somewhere where new water supplies and effective sewerage was already available, before any of the new estates had been built proper. At Mile Cross, work on some of the new road layouts had begun, along with the sewerage and water supplies needed to enable the building of hundreds of new homes to begin. Such was the hype about Mile Cross, King George V and Queen Mary made a visit in February 1921 to see these works in progress and in the below image you can see them being met by a large crowd as they entered Mile Cross from Fakenham Road (The Adsa Junction), presumably having driven down from Sandringham.

So with this in mind, it seems that Mile Cross was the area chosen in which to build these new, wooden huts, but why were huts being built here at Mile Cross in the first place, at least a year before the first ‘proper’ homes began to appear? I was intrigued (obviously). The typed document continued to shed more light; Old Arthur was becoming increasingly annoyed at having obstacles put in his way when trying to improve our grubby little city, noting that he was often delayed and partly (the word partly being crossed out and corrected in pen to read greatly) inconvenienced in carrying out City improvements because of the difficulty of providing accommodation for persons occupying houses required in carrying out such improvements. Now for those of you lucky enough to have seen the recent 100 years of Mile Cross Show: The Great Estate! I couldn’t help but re-read his objections in the report in the pompous voice one of the actors portrayed him as having in the show and I suspect they weren’t far off the mark.

The document continued: At Westlegate, Fishergate, Fye Bridge, and Heigham Watering, difficulties of the kind have arisen and the Corporation has had to purchase premises for displaced persons and recently railway-carriage has been utilized. Now this part also caught my attention as in 1934 George Plunkett had photographed a Railway Carriage that at some point been used as a dwelling at Woodcock Road, on the opposite side of Aylsham Road to Rye Avenue.

Collins continued: Other cases are expected shortly to arise. In most cases the houses affected are of a very low type. Now this is where it gets more interesting to the story I’m trying to tell here: The new houses are let at a higher rate than the displaced persons can afford and it is felt that the provision of efficient wooden houses placed in a good situation with proper drainage will afford better accommodation than that now enjoyed by the persons affected and will suffice till the time arrives when the tenant can be afforded permanent accommodation. Affordable housing (albeit temporary), whatever next?

An interesting little snippet from the records indeed, but what was it all about? Thankfully, our plucky researcher had found another document from the same ‘Housing for Flood Prevention Committee’ minutes, dated November 1922 and from the main man himself (AE Collins) which goes into a little more detail about the cost of purchasing the ‘Wooden Dwellings’: In connection with obtaining vacant possession of properties for proximate river widening works, forthwith 20 dwellings are required as substitutes for those which will have to be vacated. I know of no quick means, at reasonable cost, of supplying such dwellings other than the purchase and adaptation of sufficient Army Huts, which could be erected on the reserved two acres at the Mile Cross Estate on a site where sewerage is available. I do not know the current price of these huts; the last time bought was at £40 (he’d obviously done this before, somewhere else) but I think they are cheaper now. Probably they would be accepted as dwellings at a further cost of £90 per dwelling, making the probable cost £130 per dwelling. I am, Gentlemen, Your obedient Servant, ARTHUR E COLLINS City Engineer.

All of the points noted above give us some fairly good (bloody obvious) clues as to why there was a need for temporary wooden huts, or hutments as they were being referred to, at the edges of our expanding city. Back in the early 1920’s or the early nineteen-teens (is that a word?), it wasn’t all that long ago that Norwich had witnessed some of the worst flooding on record, created in part by some phenomenal weather conditions but also because of the way the River Wensum had been strangled by poorly-considered developments along its banks in the very heart of our cramped, little city. This fatal and catastrophic flood meant that the Council of Norwich now knew without doubt that there was an urgent need to widen the Wensum at various points to ease the flow of water through the city centre, to prevent these floods from happening again in the future. They also realised that there was a drastic need to move the people living in the somewhat-soggy firing line, out of homes that were in the more flood-prone parts of the city and into somewhere safer and more habitable, and It seems that these first people to move into new homes on Mile Cross were actually the frontiers (and you’ll see why I’ve used that particular phrase later). Moved out (in two senses of the word) to be housed in the temporary wooden huts imagined by Collins in his slightly-pompous, yet noble quest to improve the property and people’s lives here in squalid, little Norwich.

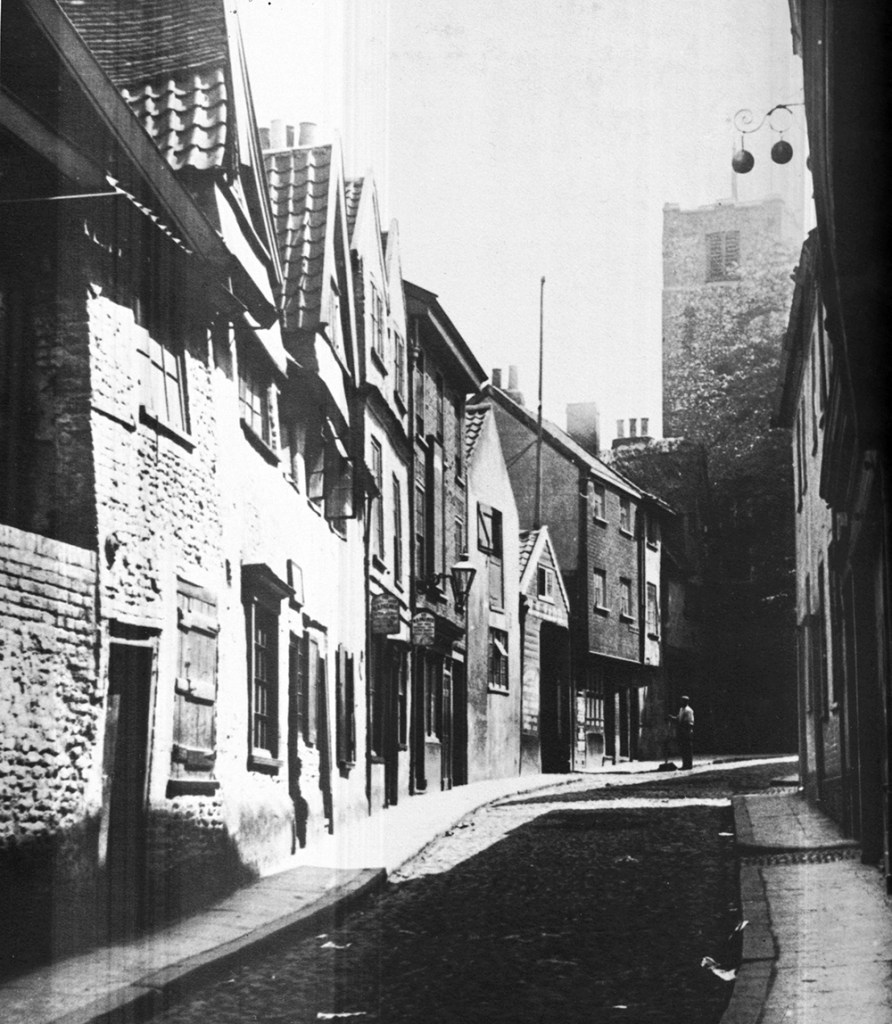

A small collection of the homes mentioned in the earlier document, were located at the corner of Fye Bridge Street and Fishergate and these needed to be cleared and demolished so that the vital river-widening could take place, along with the construction of a newer, larger bridge as this was one of the points highlighted by the engineers that were a major choke-point in the Wensum under extreme weather conditions, such as those seen in the floods of 1912. The image below, taken by George Plunkett shows part of the patch of land where these small homes were located, you can also see the older Fye Bridge and how narrow it was:

The homes referred to at Heigham Watering were a lot further upstream and in an area where the river had plenty of room, not a choke-point like the narrowest parts of the Wensum in the city centre; however, these homes were regularly under water due the low ground on which they were built, right next to the river. But this wasn’t the only reason that these particular homes were being earmarked for demolition; not only were they considered damp, squalid little homes located at the edge of a large flood plain, these homes were situated right in the way of where Arthur Collins wanted to build his fancy, new bridge to connect the soon to be built Mile Cross Estate to Heigham and therefore to the rest of the city (which can be read about by following this link).

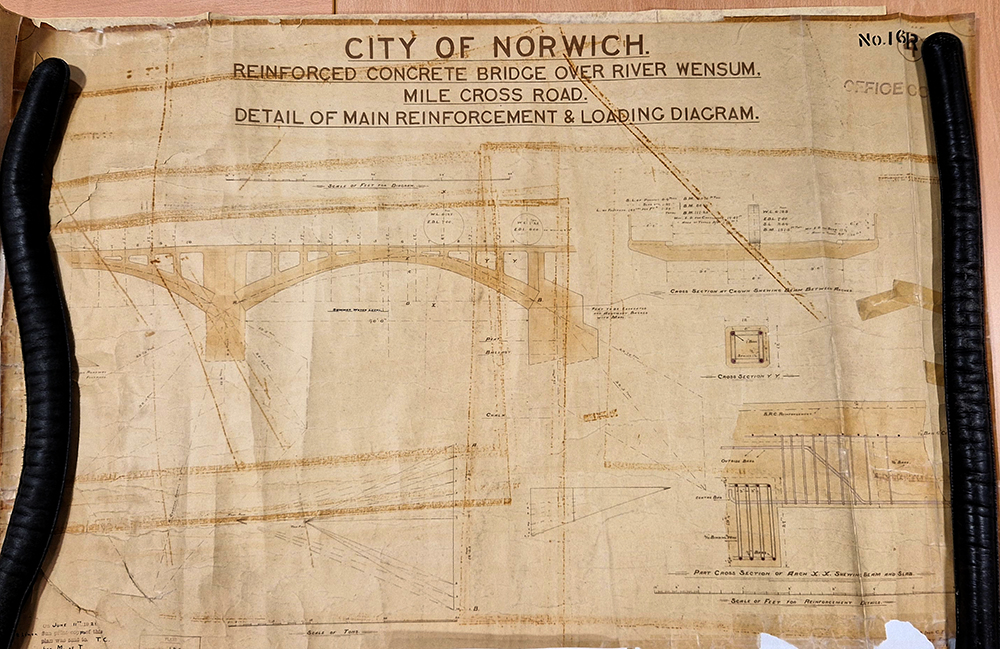

The following image is of a Technical Diagram for the Arthur Collins’ new bridge that was to be built at the end of Heigham Watering. Interestingly, not all of the buildings here were demolished, the council deciding to keep one half of Dial Square, and this unique-looking building, with it’s old sun-dial can still be admired at the junction with Heigham Road and Mile Cross Road.

The odd one out in the list of areas highlighted by Collins where buildings needed to be demolished was at Westlegate, in the heart of the city. This small collection of homes wasn’t anywhere near the river and wasn’t at any risk of being flooded, not unless they were expecting the long-lost Great Cockey (essentially a former stream that trickles somewhere deep beneath it) to erupt back into life, Which wasn’t very likely. It’s most likely that these homes were to be demolished because this part of Westlegate was seen as run-down and particularly narrow. These homes were demolished so that the bottom half of the road could be widened, and looking at the old maps this happened at some point between 1921 and 1926.

As well as the two fascinating documents discovered by our plucky researcher from the period just before Mile Cross was about to be built there was also another document hiding in amongst our research folders. This one was a few years older, and it added even more detail to this interesting pre-Mile Cross estate period, in the form of a newspaper cutting from 1919. It appeared to be a letter in response to an earlier letter published about the possible creation of these wooden huts. Unfortunately, I can’t find the piece that this is in response to, even though I have trawled the old newspapers section on the various ‘find my past’ websites, but it doesn’t matter as the response gives us a few clues:

“Sir – If one may judge solely from the report which appeared in your columns, it would seem as if the Council dismissed without adequate consideration the proposal to purchase wood and iron hutments for erection on the Mile Cross Estate (bear in mind this was written in 1919). It would appear that sixty families could be accommodated at a cost of about £250 a family, and that the erection of the cottages could have been carried out with very little delay. Now in an earlier part of the proceedings a report was given by the City Engineer (Collins) that the cost of the new Carrow bridge, if erected now, would be about £36,000, but if the erection was postponed a few years the cost might reasonably be expected to be reduced to about £28,000, a reduction of two-ninths (very precise!), say 22 per cent. One is entitled to assume that the cost of erection of permanent dwelling-houses, such as the council have in contemplation, would be reduced by at least an equal percentage if the building were postponed for a few years and probably by a greater proportion still in ten years. Now 22 percent of the present cost of sixty of the projected brick built dwelling-houses plus interest on that sum for ten years would would probably pay the cost of the purchase, re-erection, and conversion into separate dwellings of these hutments and leave the materials as profit at the end of the period. In any case, if the whole cost is not saved, the community will be in a better financial position to view the larger expenditure at the end of ten years than that at present time; if we are not, the country will be bankrupt. Let our councillors ask the people who are vainly searching for cottages whether they would sooner have these wooden houses now or wait a year or two for brick built houses at a very much higher rental. I have no doubt as to the replies which hundreds would give. Mr Wilde’s reference to wooden slums is surely a misapplication of language (what a diplomatic turn of phrase). If it refers to the materials of which the hutments are built, it is an insult to our relatives in Canada and other overseas Dominions. If it refers to the fact that the new habitations would be in a number of continuous rows, it is an insult to most of the residents in the “respectable” parts of Norwich (I think he’s having a dig at what we’d now refer to as “NR2”, good lad!) and all other towns. I do not know what the hutments are like, but I can confidently assert that a decently-built wooden house is comfortable and dry, which is more than can be said of thousands of our cottages in Norwich. It is not too much to say that there is no brickwork of local bricks and mortar which will keep out a heavy and prolonged driving rain, and that 75 per cent of the existing cottages and small house in Norwich which have exposes walls facing anywhere from south-west to north-west, have, at least, one damp bedroom. apparently the mad craze for expenditure which the war has generated has infected the Council. Yours &c., ERNEST I WATSON. Norwich, 23rd October, 1919.“

As of yet, I can’t figure out who Mr Ernest I Watson was other than that he was a Doctor of Laws and Solicitor based in Prince of Wales (and living at Clarendon Road) who liked to air his opinions by writing letters to the local rags, often in response to others he disagreed with. He did, however, seem to know what he was talking about, opining on subjects such as; Housing, Rental prices, Voting, Poor Law relief, Outdoor relief, Taxes, Health Charity, and he also had a particular interest in Pub licencing and alcohol.

It appears that in this instance he had taken offence to an earlier letter, where the unknown (to us) writer had been moaning about the cost of providing people in need of somewhere to with these temporary wooden huts in Mile Cross, and then comprehensively taking them apart on the subject. After delving deeper to see if I could find out any more on the old newspaper websites it appears that old Ernest was a prolific contributor to the opinion pages of the local rags.

This out of context letter made me chuckle: To the Editor. Sir – I have no particular desire to have the last word with Mr Starke. I will leave it to your readers (if any of them are sufficiently interested to re-peruse Mr Starke’s letters and my last) to determine whether my criticism was not absolutely justified – Yours &c. Ooh, get you! We tend think that ‘back in the good old days’, before the internet and more importantly before the days of (anti)social media, there were no comments sections in which people cold argue, snipe and collide intellectually (not that you get much intellect in the comments sections, these days…), but there was, it just happened in the letter pages of our local rags, with the tit-for-tat exchanges lasting weeks rather than minutes.

Back to the huts/hutments (or wooden slums). It appears that they were important enough to have caught the attentions of another great, local photographer, Clifford Temple. He’d ventured out of the city centre to capture one of these rows of wooden hutments, just before they were to be demolished in 1932. I have been aware of this photograph for some years now, and when I first spotted it, part of my brain wondered what they were all about, but I must have filed it away to think about at a later date. Finding these documents hidden away in our research archive answered my question and reminded me to do a bit more digging. By taking a closer look at the image in photoshop, and partaking in my favourite pastime of looking at the details hiding in the background of old photographs, I can tell that these two particular rows of hutments were located on the north-eastern most end of Rye Avenue. The brick house in the background on the left being number seven Boundary Road, and the houses in the distance on the right being the backs of houses at Spynke Road. You can also see in this image that the each row of huts comprise of at least ten small units on two levels. They are also looking a bit neglected, especially on the right-hand hand-rail, most likely having been already vacated in anticipation of being replaced by a collection of the newer ‘phase 2’ houses, similar to those seen dotted about the estate filling in some of the random gaps around the estate, such as at Fenn Crescent and the rest of the Mill Hill extension, at end of Bowers Avenue and Gresham Road and another pair filling in a gap on Drayton Road just north-west of the shopping parade.

In this next image, taken from the air, we can see most of the huts situated at Rye Avenue, Marshall Road and Sandy Lane (or Boundary Road as we now know it). I’ve looked at this image hundreds of times in the past as it forms part of a larger, almost-iconic image of Mile Cross, focussing in on Appleyard Crescent (or as some people call it, The Millennium Falcon), but I’d never noticed the once mysterious (to my mind at least) huts, hiding in plane view in the very top right of the image, probably because I’d never thought to look until now, and partly because the original negative is damaged here. I’ve zoomed in and highlighted the huts in yellow, and they tie in with the location of the huts recorded on some of the old maps. From up here they look considerably smaller than the newer, permanent brick houses that are still standing strong a century later.

Although I still don’t really know who the first family or person was to move in to the brand new Mile Cross estate, I can pinpoint where the very first families actually came from. They weren’t moving into any of the fancy architects show houses, or into the lovely ‘Dorlonco’ cottage-style houses, these early ‘Pioneers’ if you will, had moved into a collection of wooden hutments right up by the Boundary and came from some of the most compact and/or increasingly damp parts of the City Centre and out to the once-distant edges of the far-flung Norfolk countryside. It must have been a bit of a (perhaps welcome?) shock to the system. Hardly the ‘wooden slums’ dreamt up by some wealthy commentator in the local rag, but hardly a vision of the much-vaunted architects houses built by the likes of Wearing and Skipper, either.

Thanks for reading,

Stu

Thank you, I enjoyed reading that. Rod

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi,

Fascinating reading your articles on the Mile Cross Estate.

My grandparents moved from Wymondham to Norwich and first lived in a council house on the Catton Grove Estate from around the early 1930s as far as I know. My mother went to the Catton Grove infants aged 5 in 1935 and her next school was at St Augustin’e Primary when they would have moved and been living in Collins Court on Angel Road. I am curious to know whether this group of houses was named after Arthur Collins by any chance as he seems to crop up a lot in your article below? My mother is no longer alive so I can’t ask her any questions now although I do have quite a lot of her early life recollection notes which she wrote down for the family.

Look forward to hearing your comments.

Kind regards,

Richard

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Richard,

Having taken a look, I think you’re right. He would have definitely been involved with the creation of the Angel Estate, and two of the adjacent roads are named after his colleagues. Arthur Collins was a fascinating man, and a friend of mine is currently writing a book about him, so it might be worth keeping an eye out for it.

I’m glad you’re enjoying The Mile Cross Man page,

Stuart

LikeLike