A few months ago I was contacted by a chap named Robin Clare who told me that he had in his possession a booklet and a collection of photographs that may be of interest to a man like myself. The photographs were taken during a street party laid on by the residents of Glenmore Gardens to celebrate the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. The event, which took place a week before the actual event, looks as though it was a very well organised affair and required two separate committees to help organise and run it. These committees were made up by residents of the gardens and their roles were to appeal for help and funding for their planned celebrations. Thankfully for them the response to their appeals were very successful, with local businesses, tradespeople and local residents being very generous with their offerings.

The day’s events unfolded as follows; the young children were taken to the Capitol Cinema, just around the corner on Aylsham Road where they were treated to free Ice Cream and treated the the Children’s Matinee Show where they enjoyed a programme of Children’s Films. Whilst the Children were away, the Men’s Committee decorated the Gardens with flags, bunting, balloons and all manner of festive decorations to create a “Gay Arena” with a replica of the St Edwards Crowd in the centre and the Ladies committee laid on the food (how very 1950’s!), although it appeared that to the concern of many of the residents that the angry-looking skies were going to ruin the whole celebration. One adult even knelt on the green, offering a prayer for the rain to stay away. It’s hard to picture doing something like this in 2024 and it shows us how very different the world was back then. Thankfully the prayers were answered and by the time the children emerged from the cinema and back into Glenmore Gardens to witness the colourful scenes laid out for them whilst they’d been away, the clouds had cleared and covered the scene in glorious sunshine.

The photography, which can be seen below, was provided by a photographer going by the name of ‘K. Jay’. Unfortunately, I can’t find any references to a professional photographer going by this name, which is a shame as it would have been nice to see what other images of Norwich they might have captured during this era. It might have just been a local with a camera, either way, the photographs were taken by someone who obviously knew what they were doing and with an expensive bit of kit for the time. There was also a cine camera on the scene, so there’s probably a video of the event hidden away in a dusty attic somewhere.

In the below photograph of all the children assembled on the green in their various costumes you can see that it was a very well attended event by the children, some of the costumes being a bit ‘iffy’ by today’s standards. Especially that of the overall winner. We do have to remember that the world was a very different place back in the 1950’s.

I’m always going on about how I love to delve into the background of an image and in the above image, It’s nice to see a snippet of post-war Glenmore Gardens suburbia in the background. Apart from the lack of cars parked everywhere and the roads now needing yellow lines, it hasn’t changed a great deal, although you’d struggle to assemble such a large group on that green today due to the added plants and bushes.

Not only did the committees arrange and run the street party, they also created a souvenir Coronation Booklet to celebrate the day of the Glenmore Gardens Children’s Party and it looks like a lot of effort was put into its creation. This one belonged to Robin Clare:

The page below gives a little detail into how the day’s events were planned:

As the last paragraph of the page above mentions, after the hungry children had eaten all of the food and made a bit of a mess in the process, they then went home to get into their fancy dress for The fancy dress parade which was to begin at 1730:

As we can see from page 4 there were quite a few prizes for the children, although I’ve had to blank out the winner as it is offensive by todays standards. However, like I said above, this was over 70 years ago, and the world was a very different place back then. That aside, it is a part of our history and we can’t let that detract from what appeared to be a lovely event for the children of Glenmore Gardens. As we can see by the text at the bottom of the page, even the children who didn’t rank in the top three for each category received a small prize for their efforts, which was a nice touch. There were also some prizes for decorated bicycles.

The end of the celebrations were marked by the playing of the National Anthem at 9pm, and as noted on the page below, the children were taken home to bed and the parents wended their way to the a “well known local place of refreshment for a well earned revivor”, most likely the Kings Arms Pub, which was connected to Glenmore Gardens via a handy alleyway.

An interesting note from the page above is that as well as the children from Glenmore Gardens, four boys from the Woodlands Orphanage were also invited along to enjoy the celebrations. The Woodlands Orphanage (also known as the Woodlands Children’s Home) had opened a couple of years earlier, in 1951 and stayed open until 1974. The home was located off Dereham Road close to Sweetbriar Roundabout.

The admin behind the party, note how a Mr Clare, Robin’s father, was unanimously elected to the chair. More on him later:

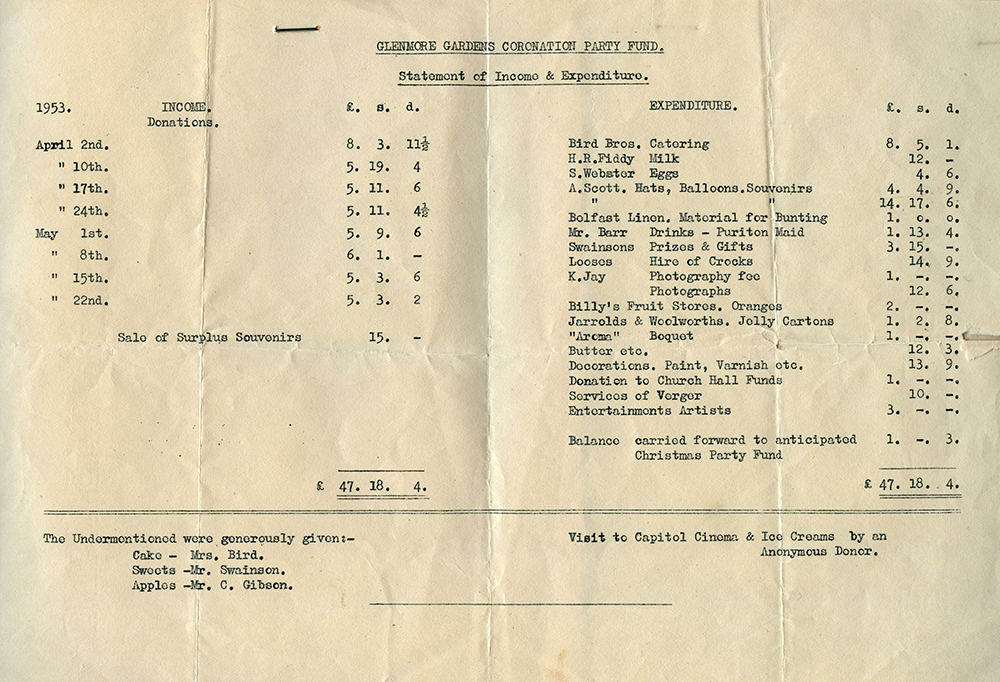

The following image showing the document titled ‘Glenmore Gardens Coronation Fund’ shows how well the whole event was run and gives a very detailed breakdown of the costs involved and how many local people and businesses were involved:

There’s some names on that list that will be familiar to some and some interesting donations, such as; Jelly Cartons from Jarrolds & Woolworths, Hire of crocks from Looses and Cake from Mrs Bird of Birds Brothers. There’s also the visit to the nearby Capitol Cinema including Ice Cream paid for by an anonymous donor.

As is the norm these days when I’m looking into the post-war history of Mile Cross, we’re never too far from finding some unexpected Prisoner Of War stories and this is the case here. Not only did Robin have all of these wonderful photographs and the booklet, he also had some fascinating documentation that told a story of how his father been a Prisoner of War before being given the keys to a home in the newly-built Glenmore Gardens:

Robin Clare’s father, Peter had like many of the men from the Mile Cross area, had gone away to join the fight overseas and it appears that not long after he left the UK on a boat headed towards the Middle East his wife, Peggy, discovered that she was pregnant. Not knowing his exact location and it being the 1940’s there was no real way to get word to him in any sort of a hurry. Shortly after, he was captured and reported missing, presumed dead. Imagine that news, especially under the circumstances, it must have been heart-breaking. Despite this awful news, Robin’s mother never gave up and kept writing to him in the hope that maybe he was still alive and that her letters might somehow reach him, probably mixed with a bucketful of grief and denial. However, it appears that her eternal hope had not been in vain and after two years in captivity Peter did start to receive the letters sent out in hope form the UK by Peggy but they were arriving in no real order. The jumbled order of these letters meant that Peter had no idea who the little girl was that the letters were referring to and the following collection of documents help us to understand what had happened, not something Peter or Peggy had the benefit of having, and it must have been an awful situation for all concerned.

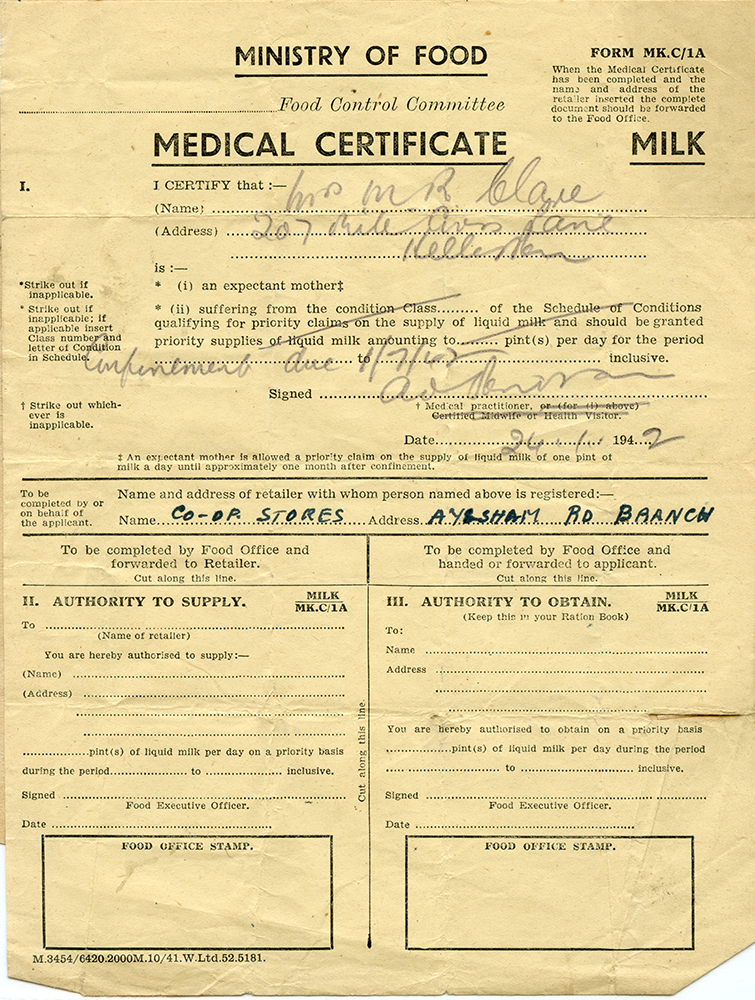

The earliest document supplied to me by Robin was this Medical Certificate from the Ministry of Food that shows us that Robin’s mother is “(i) an expectant mother” and therefore will soon be needing extra rations. “An expectant mother is allowed a priority claim on the supply of liquid milk of one pint of milk per day until approximately one month after confinement“. The pencil-written note saying that a follow up appointment is due on the 1st July, 1942, almost 5 months after the certificate was dated. It seems that the Co-Op Stores on Aylsham Road was the place where the family collected their rations.

Unfortunately for Peter, his situation was about to take a turn for the worse, and any communications sent to him to tell him that he was to be a father never made it through due to the quickly advancing Japanese Armed Forces, battling their way towards Singapore and disrupting lines of communication.

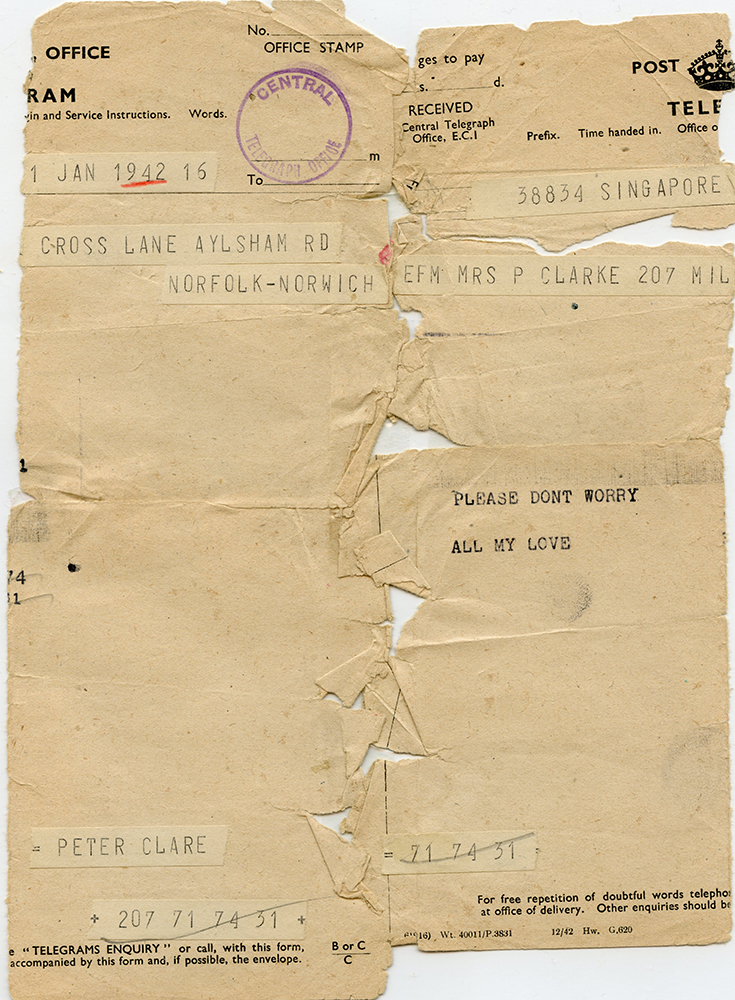

Peter had managed to send out some correspondence in the meantime, although the message was a short and sweet New Years message to the family. “Please don’t worry. All my love, Peter“, as seen below, dated the 1st of January, 1942:

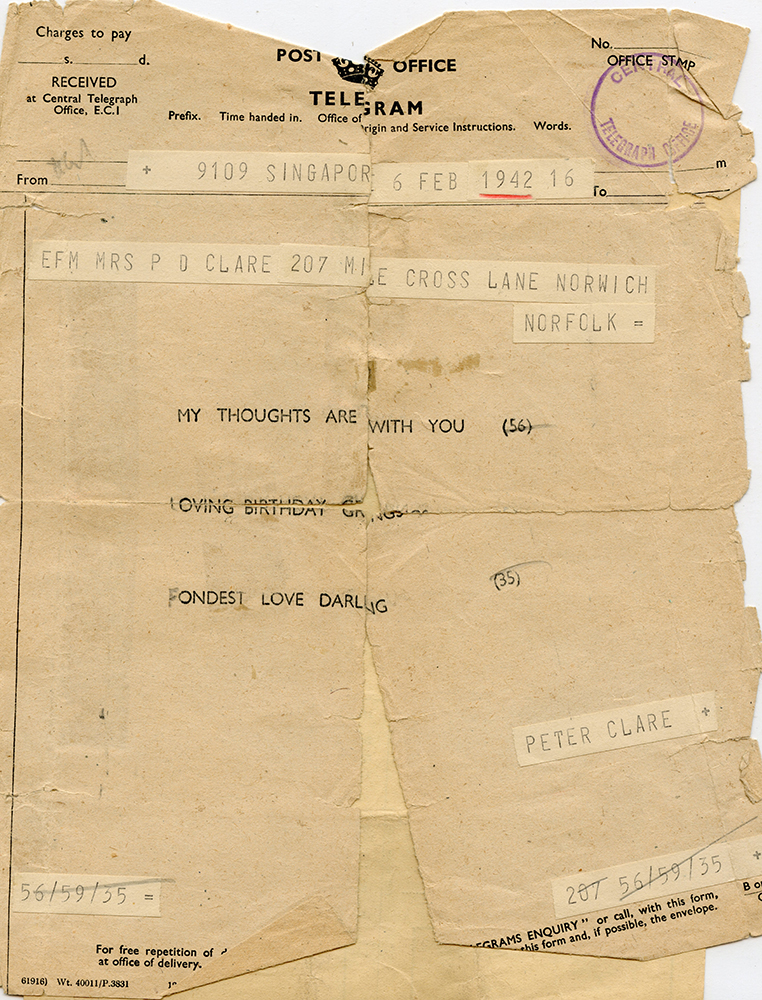

This following message seems quite poignant, considering the date, and that it would be the last wilful message to be sent home for a while. Peter must have known by now that the Japanese were getting close and that the situation in Singapore was looking less than favourable for the allied troops trying to defend it. It’s dated the 6th February, 1942, just two days before the beginning of the end and the start of the soon-to-be successful Japanese attack and their capture of over 80,000 prisoners of war, including Peter Clare.

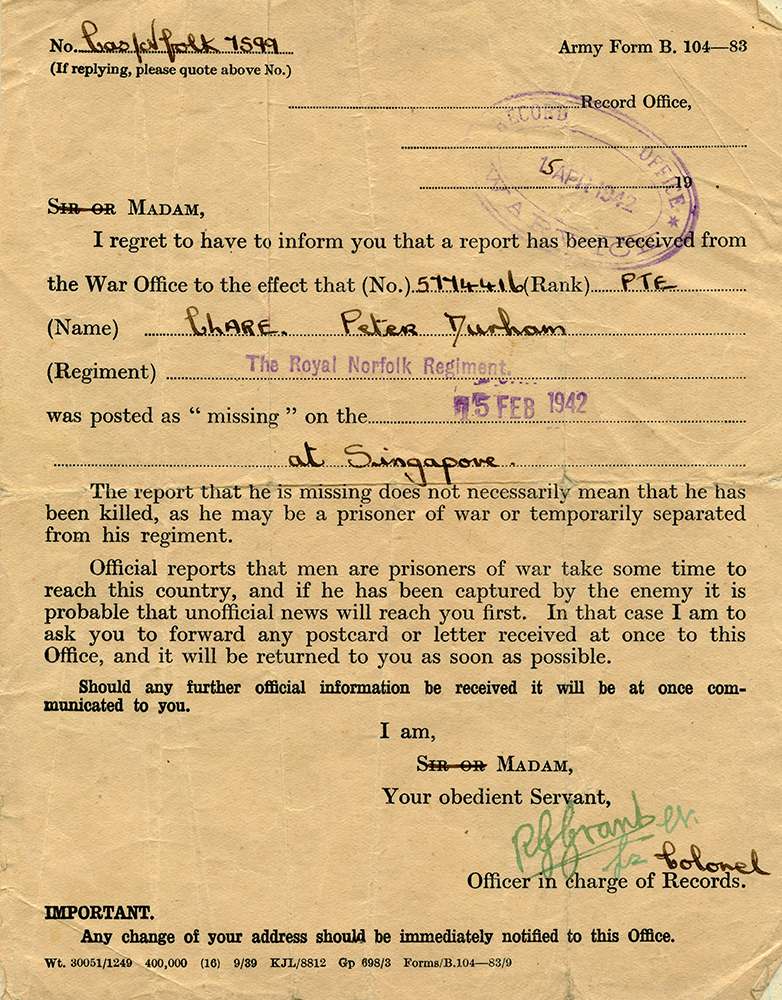

The next piece of correspondence to come through must have come as a terrible shock. Peter has been declared ‘missing’ and the date ties in with the surrender of the British forces to Japan on the 15th February, 1942. We can only imagine at how the family must have felt with this news, although they must have had a bit of time to mull over the mystery, seeing as the message didn’t turn up until April. Imagine receiving a message like this and having no means of reply or not knowing for certain what had really happened to your loved one(s). The line that really hits home to me is as follows: “The report that he is missing does not necessarily mean that he has been killed...” It must have been agonising for Peggy, but it seems as if it was this particular line that also gave her some much needed hope. What really strikes me is that there would have been over 80,000 similar telegrams sent to other families across the empire in a relatively short period of time. Roughly 27% of that 80,000 would eventually die in captivity.

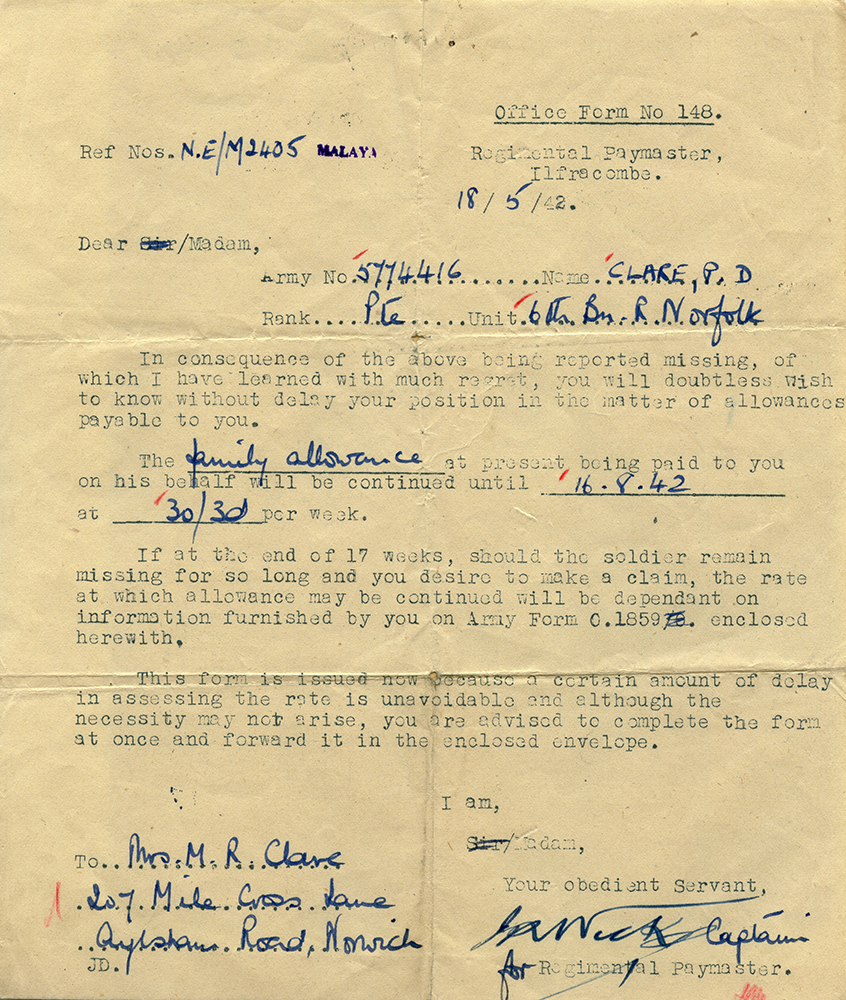

After the rather cold and matter of fact message sent back in February, a follow-up message was received in May from the Regimental Paymaster, regarding a Family Allowance payable as a consequence of Peter being declared ‘missing’, although it seems that this will only be paid until August when if Peter was still reported as missing, Peggy would need to submit another form for continued payments. This tells us that Peter’s fate was still unknown at this point,

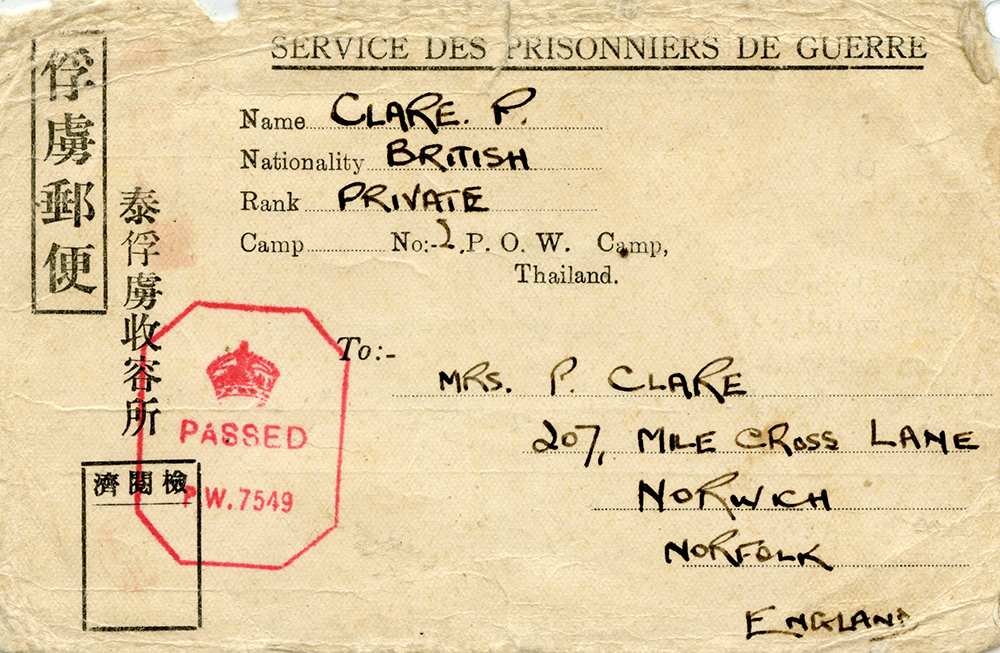

The next small, but very welcome piece of correspondence came some two years after the fall of Singapore and it was sent through by the Japanese. The details are scant and you can see that the Japanese weren’t allowing any real information out, other than the fact that he was alive and not in hospital, thankfully for the family back home there were no hints as to the horrific conditions these poor prisoners of war were being forced to work and die under.

It appears that Peggy sent the card on to the Infantry Record Office to give them notification that Peter was still alive, albeit in captivity, which was returned with the following document along with a P2327B leaflet that appears to have given instructions on how to communicate with POW’s officially:

The P2327B was a leaflet that was actually created by The Post Office as a means for families to communicate with POW’s effectively, and this leaflet gave detailed guidance on what to write and how to write it so that the Japanese would allow it to be sent through to the POW’s without censor or going straight in the bin.

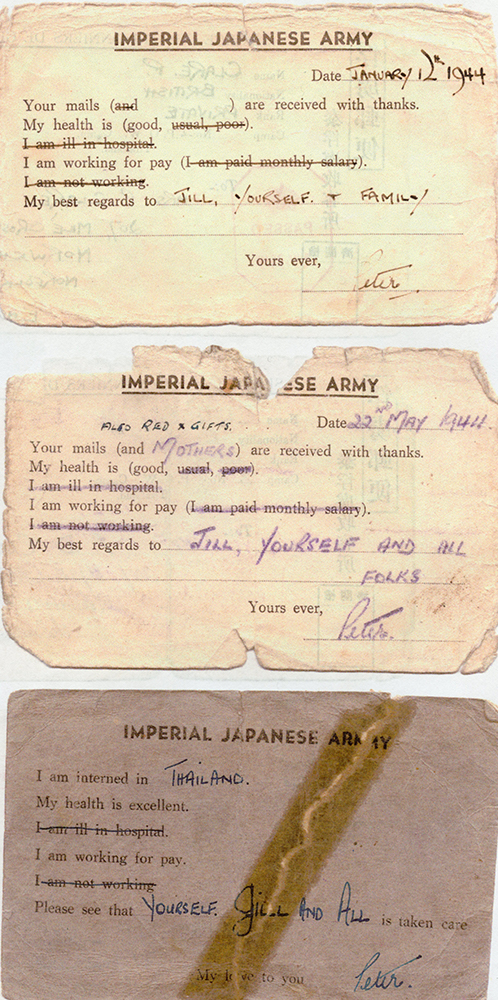

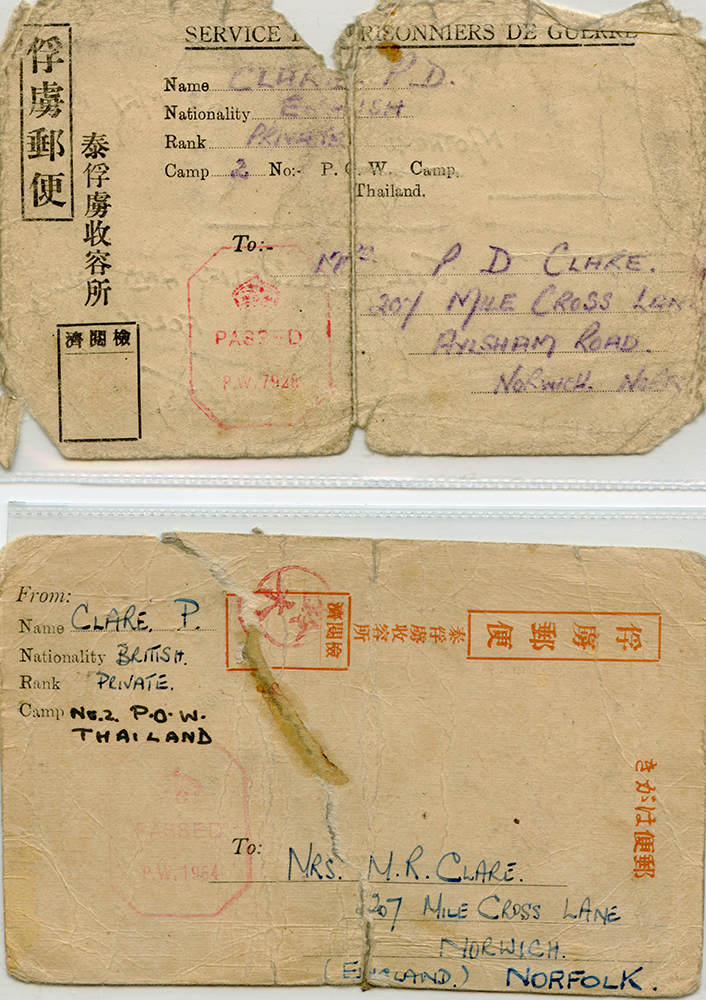

The following documents (which include one of the ones above) show that further communications were now getting through, although it doesn’t show us here that Peter wasn’t receiving them in any real order. One of the cards stated that he’d been interned into a POW camp in Thailand:

The envelopes show us that Peter was being held in Camp No.2, known as Songkurai, which was a notorious place to have been held captive by any stretch of the imagination.

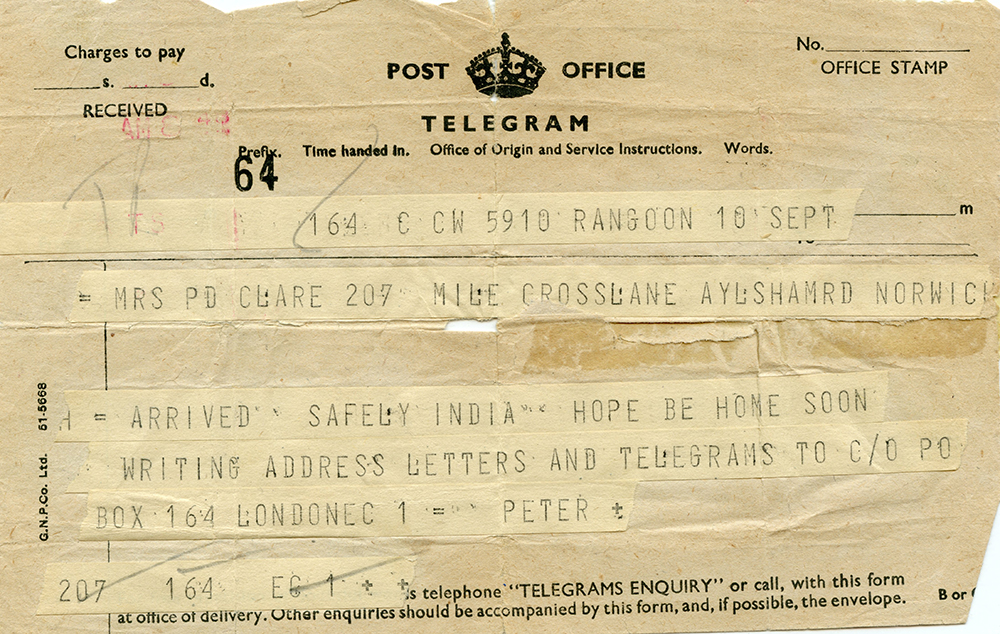

This next document must have come as a massive relief to the family, and interestingly it’s dated just eight days after the surrender of the Japanese to the Allies. That must have been one hell of a week for young Peter, having been rescued, given much-needed medical treatment (these poor POW’s were little more than walking skeletons) and then shipped across to India, where he had a chance to wire home a short message: “HOPE BE HOME SOON”. It’s hard to comprehend what a rollercoaster that must have been, but we also have to remember that many never made it out of these camps alive.

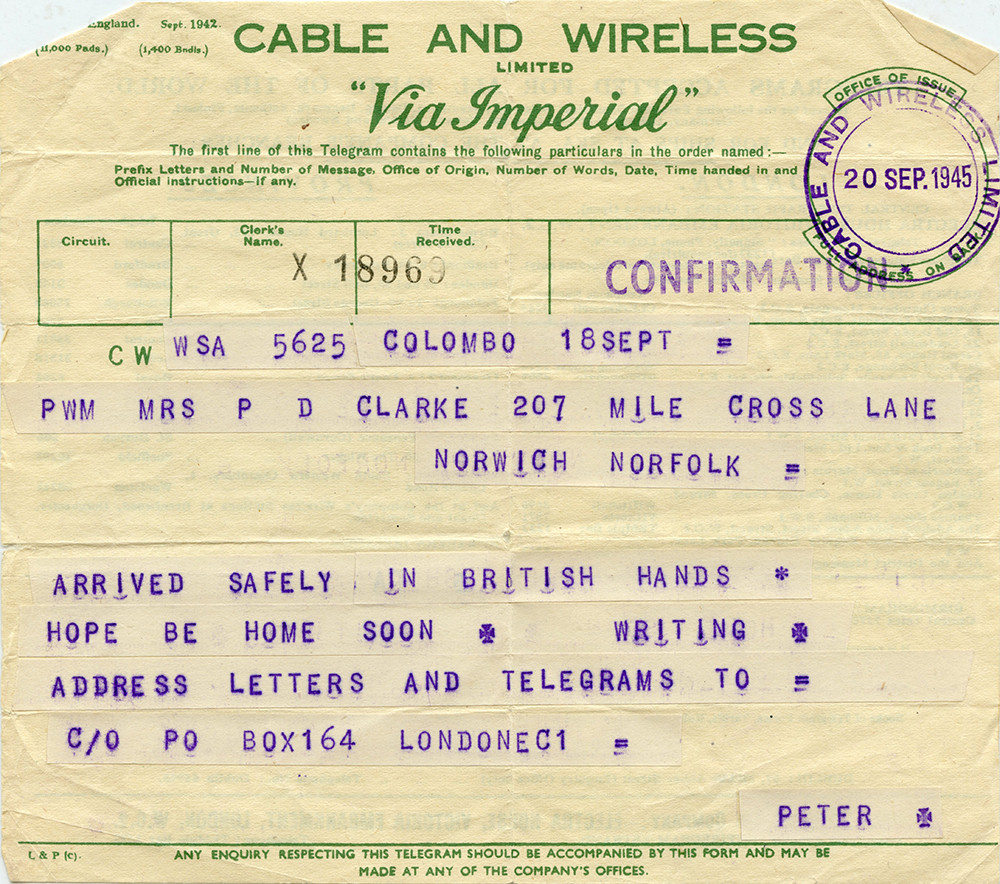

Although it appears that his message then took another ten days to make it’s way back to Mile Cross, via this official Cable and Wireless “Via Imperial” telegram, note how the name has been mis-typed during the process, unsurprising when considering how many of these telegrams were being sent at the time:

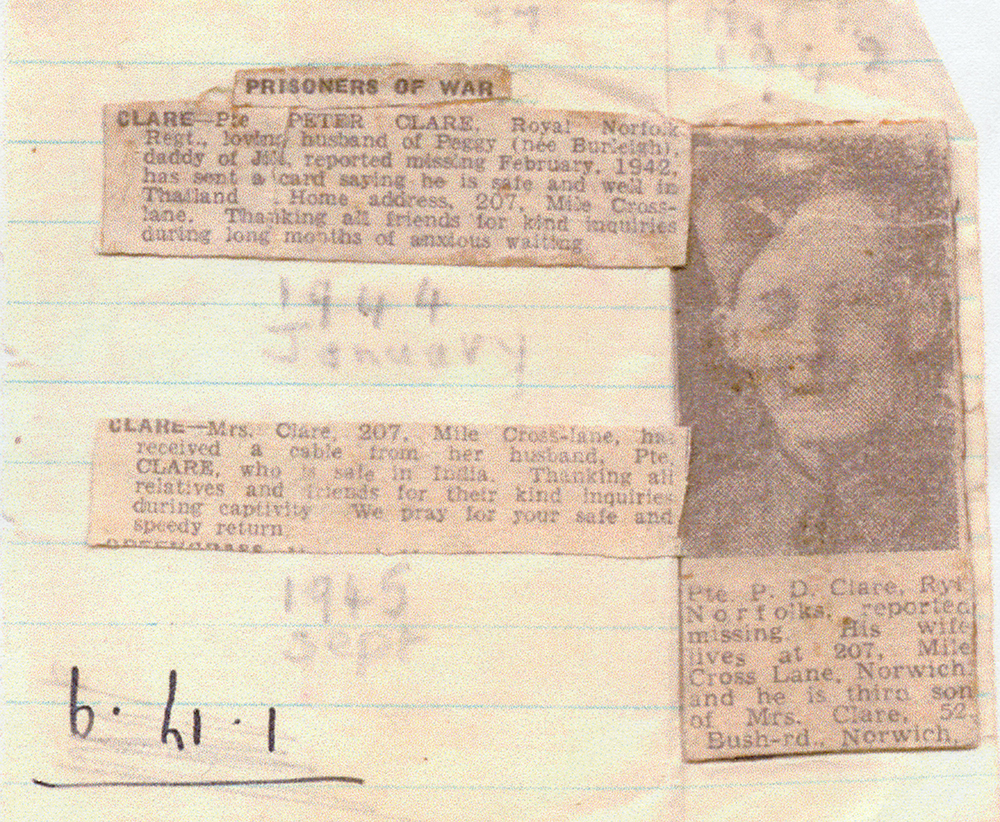

Robin also had a selection of paper cuttings, presumably handed down to him by his mother with a picture of Peter taken before he went to war documenting his capture and release. It’s nice to see what Peter actually looked like, although I suspect that he was looking a lot more gaunt than this when he finally arrived back home to his beloved family.

And a better picture of Peter, scanned from another cutting:

Not too long after Peter made it back to Mile Cross to meet his enlarged family, and rebuild his life he and his growing family were given the keys to their new home in Glenmore Gardens and the story goes full circle.

The world was a very different place back then, but at the same time it was completely familiar to us recently descended from those generations. Bearing in mind what those generations had gone through and the fact that nobody was ever too far from the shadows cast by the clouds of war, and you can see why Patriotism was almost at a fever pitch after almost 50 years of fighting. The Royal Family were seemingly more mysterious back then, too and it’s fascinating to look back and compare the moods with those of today. It impacted my generation too, to some extent and I still remember living in fear of being blown to atoms by ICBM’s loaded with nuclear warheads. I vividly remember being made to watch “When the wind blows” by Raymond Briggs during a lesson at either Dowson Infants or Mile Cross Middle School. The world moves on and things change and there’s a familiar inevitability to that, but I’m thankful at least that my own children have never really had to live under such circumstances. Long may that continue.

A big thank you to Robin for getting in touch to share his family’s history and giving us a fascinating insight into our local history, and for inviting me into his home and supplying me with copious amounts of tea. Once again the history of Mile Cross has led us back to the war and the affects it had upon the residents here, and this probably won’t be the last piece about Glenmore Gardens and the War as I have another story lined up for the future, so watch this space.

As always, thanks to you for taking your time to read my ponderings, and if you have a Mile Cross or Norwich story you think needs telling, and that I’m the man to have a go at it, please get in touch.

Stu

Thanks for this Stuart, The Mile Cross Man

I have copied in Mile Cross primary in case they don’t get it.

Bert

LikeLike

Thank you so much for posting such an informative article on Glenmore Gardens and the horrendous account of Mr Clarke and his WW11 experience’s. Well done 👍👀

LikeLike

Thanks for the post. I grew up in Glenmore Gardens and had heard about the Coronation party that took place. What’s more amazing to see is the party table laid out right in front of my childhood home!

LikeLiked by 1 person