A while back I wrote a piece about a house just around the corner from mine that had stood empty for a few years (click to read). This house had barely been modernised over the years, and the more I delved into the history of this one particular house, the more interesting it became. Often is the case when researching your local history, following your nose often leads you down historical alleyways that you never expected to end up in, and more often than not, they end up being more fascinating than you ever could have imagined. And it’s this kind of follow-your-nose research that the MX100 research leads, myself included, had been teaching our fellow citizen researchers as we encouraged them to dig for interesting snippets of the estate’s history for the recent Mile Cross 100 project. Another part of this process was also asking for the public to provide us with their own stories about Mile Cross.

Leading by example, I pulled a few strings on some of the Facebook memories pages to try and stir up a bit of interest for the project, but this next story actually came via an email exchange with a long-time reader of this Mile Cross Man website, Garry Todd, who a while back had contacted me to let me know that his grandparents had lived in the house directly opposite mine, and that somewhere in his possession there was a tin full of old photographs that when he got the chance, he’d have a dig through to see if he could find anything that may be of interest to a chap like me. The Facebook call to arms reminded Garry about our previous conversation from a couple of years ago, and I must admit that I’d pretty much forgotten about this earlier exchange. We all know how insane the last couple of years have been and how that time seems to have been stolen from us all; pick-pocketed by time, if you will. So, it was a pleasure to receive the follow-up email.

Garry had found an image in his collection, taken way back in 1946 of his step-nan (father’s side), stood at her doorway posing for a photograph whilst holding her pet dog. He wondered if I’d be interested in seeing it, noting that seeing as it was taken literally across the road from here, and that as I see that scene every single day, every time I leave my garden or look out of my living room window, that it might not really be of interest… Of course, I was interested in seeing it, these little photos can tell us so much, and often, these seemingly-ordinary snippets of life tend to lead to something extraordinary, even more so when they are literally on your own doorstep. Garry kindly sent over a picture of the old photograph, and I found it instantly fascinating. I asked if I could scan it for the MX100 project backed up with a little bit of historical context, as it would be the perfect example of one of the little snippets of Mile Cross History that we were looking for, for the Mile Cross 100 Story Map (Humap) website that me and my fellow researchers were (and still are, until February 2024) creating, or to appear in the up and coming Mile Cross 100 year anniversary book that has taken up so much of my spare time of late.

So taken aback was I at this wonderfully-posed photograph from a seemingly-unimaginable time (for someone from my generation), I decided to invite Garry round for a cuppa so that he could share his memories behind the photo and to see if I could dig for a little more Mile Cross History whilst I had his attention. Thankfully Garry agreed, and he turned up a few days later armed with some fascinating photographs, that to Garry were seemingly ordinary photographs from and of his family’s past, not much interest to anybody else other than family, but to a chap like myself, they were absolute gold. I mean, who wouldn’t want to see what their very own street looked from a time you could only imagine, or a time you’ve only been able to read about? This was the mirror image of my own doorstep, but from 30 years before I was even born, when my own neighbourhood was coming to terms with a new world that for the first time in six long years years was no longer at war with one of its closest neighbours and closest European siblings.

Hilda had lived in the house opposite from 1944/45 to the mid 1960s. Long before I moved in opposite, and to be fair well before I was even a twinkle in anybody’s eye. Hilda lived across the road from my future self with her husband George (who had 9 children all born 1911-1930 from previous marriage) and Hilda had two sons from a previous marriage. Luckily for their small Drayton Estate home, only three of these children lived with them as teenagers. To be fair, It’s hard enough living here now with two teenagers. Like a lot of the men living on the estate in this era, George had seen service in World War One, first in Gallipoli, where he was wounded in forearm, then in Palestine and then again at the Somme in France. With that track record, he must have been very lucky to have made it home at all. So it was surprising to learn that not being content with all that jeopardy, George also lied about his age so that he could serve again in World War Two. Fortunately (or unfortunately, depending on your take) for George, his patriotic plans were foiled, and after being found out he had to serve in the labour/ medical corps, instead of on the frontlines. I imagine he was still happy to have been a service to his country in one way or another. George died at 2 Pinder Road in 1963 aged 83, and in his final months he liked to sit up at the bedroom window opposite my own home, propped up comfortably enough in his bed so that he could watch the world carry on whilst he could still enjoy it. I can’t unimagine that when I look across the road and take some sort of comfort in the hope that his spirit approves to my presence here long after his passing. Hilda soldiered on for another twenty years without him, finally passing away in 1983 at the ripe, old age of 85.

Another Photograph in Garry’s collection, really caught my attention; taken in the 1950’s in the playground of the Dowson School, (that would later become the Dowson Infants and Mile Cross Middle School), a school that I attended myself in the 1980’s. Again, Garry thought that it probably wouldn’t be of too much interest to me as it was just a school photo, but he was mistaken. Not only was it a lovely 1950’s-era photograph of the children and their teachers, it also showed the area now known as Vale Green, before it was houses and flats, it also showed parts of Sloughbottom Park that were still a Gravel Pit and as well as all that it showed the industry of the waterworks on the horizon, details that I’d only ever imagined by the medium of one-dimensional maps. Now, if you’ve spent any time reading the pieces that I’ve written on this website over the years, you’ll know I can get lost in a map, but I can disappear for longer periods still in the background of a photograph, and I’ll go into that in a bit more detail below.

The main subject of the photograph was fascinating in its own right, a snapshot of my former school taken thirty years before I was led, bewildered through the very same gates, but a far cry from how it was in the 1980’s. Garry can be spotted to the immediate left of the teacher on the left, and I even found a pair of twins hidden amongst the children’s’ faces after spotting the same T-shirt on two different children. See if you can spot them. The teacher’s expressions are fascinating too. It almost looks as if they were photographed yesterday, and you rarely get that when looking at people photographed almost seventy years ago.

As lovely as the image is, I was immediately drawn to what I could see in the background, and the crops below give up a little more detail. The first of which showing the back wall of one of the toilet blocks, which were demolished well before I attended the school in the 1980’s, and and what looks like a gravestone is actually one of a pair of drinking fountains. Apparently the boys used to like leaving a frog in the one used by the girls, which is a lot nicer than what some of the boys used to do in the newer drinking fountains that were in the playground when I was a kid! Also of interest is a small building in the middle distance that stands not too far from where the modern-day BMX track is situated at the back of Sloughbottom Park. This small building was connected to a gravel pit that was still in use at the time and the wall or fence that can be seen in front of it was a lane that ran towards it from the bottom of Parr Road. something until now I’d only ever seen on a map, and something I’d never imagine I’d ever see a photograph of.

The next crop is looking at an open green area running down towards the railway line and river, and the chimney of one of the steam houses of the Heigham waterworks can be seen in the distance. This open area at the bottom of the lush, green Wensum valley was soon to be taken over by the Council Works depot and newer post-war council homes at Vale Green. You can almost feel how rural this part of Norwich and Mile Cross must have felt back when the estate was first built. This was literally at the edge of the countryside, and to some extent, still is, if you head west.

The following crop shows another part of the green space between the school and the river with an abundance of trees. This area was soon to be covered over with rubble to make it suitable for constructing buildings on top of the marshy valley bottom. This rubble came from the slum clearances of the 1920’s and 1930’s and then from the bombed buildings in Heigham. Victorian landfill. Thankfully, the infilling only came this far, stopping just in time to save what was left of a very important and very rare habitat for wildlife, not just here in Norwich, but in the whole of western Europe, Most of the Sweetbriar Marshes and the rest of the Wensum Valley were thankfully spared, just in time, giving us lucky Mile Cross residents an important and rare SSSI (Sight Scientific Interest) right on our doorstep. If you go across the little bridge that leads you from Sloughbottom Park and out on to Marriott’s Way you can see where the rubble infilling ends and the saved marshes start and it really shows you how much infilling happened from here and towards the city centre. The ground rising 10-15 feet in an instant. If you’re brave enough to clamber down the bank next to the dyke and dig in to the side of it, there’s much treasure to be found for the budding archaeologist, from Victorian china, to remnants of the slums of Norwich.

Fascinating stuff, but this wasn’t the end to the surprises hiding in Garry’s tin of seemingly-ordinary photographs, and the next images to be offered up by Garry were of a V.E. (Victory in Europe) Party being held in the middle of Pinder Close, taken in April 1945. Far from ordinary scenes in any sense of the word and such a lovely (and very rare) snapshot of Mile Cross emerging from the second world war. There’s a lot of happy faces of children who probably didn’t fully understand what was happening outside there homes and you have to remember that most (if not all) of their young lives had been lived in a state of world war, something somebody of my generation can thankfully never fully appreciate. You’ll also notice the absence of any men in these photographs.

Next up is another image of the same VE Party being held at Pinder Close with lots of smiling faces. Five, long years of war were finally over and you can almost feel the sense of relief coming out of the image. I can only attempt to imagine how it all felt for the youngsters, but I was also beginning to wonder how the women were feeling too. Where were there husbands?

Garry had yet another picture of the Pinder Close VE party and If you look closely at the picture you can see more than celebrations, there’s a range of emotions to seen on these faces, from happiness to bewilderment and some obvious trepidation. It may have been a celebration, but some of those mothers and children were still missing their husbands and fathers. The more I looked, the more I could feel it.

Just as I was beginning to wonder about the men were as I scoured these images, Garry pulled something out of his bundle of papers and photographs that would give some real insight into my wonderings. Now, there’s an age-old saying that “Norwich is a small place”, and this rings very true for Garry’s family here in Mile Cross. Not only did a set of his grandparents live at Pinder Road, his other set of grandparents lived just around the corner at Pinder Close (in the until-recently un-modernised the house that I’ve written about previously). Norwich is a small place!

Henry (aka Harry) and Ivy Scotter’s Pinder Close home is probably in the background of one of the VE street party pictures above, however, Henry was far away from these jubilant scenes going on in the street right outside his home, instead languishing in the notorious Changi prisoner of War Camp, Singapore, and he wouldn’t be coming home any time soon. Below is an image of the recording of his capture by the Japanese in Singapore:

The next news the family would hear of their father’s fate wouldn’t arrive for another five months after the Pinder Close Street party, and this next image is of the telegram received by his family on the 24th October, 1945, and sent by Harry, arranging a date to come with the children and meet him at Thorpe Station at 6pm. It’s hard to imagine the emotions that would have been felt by all when sending and receiving this telegram and it’s even harder to imagine how emotional that one reunification must have been for this particular family.

Henry Scotter was captured in Singapore and sent to the infamous Changi, known for the cruelty by the Japanese captors, which housed as many as 50,000 at any one time. At least 850 prisoners were known to have died in captivity here, but Henry Scotter was one of the lucky ones to make it out in one piece, not that he came away unscathed, far from it. Garry mentioned that his Granddad not only having to be treated for Tropical diseases at Roehampton, he would have live out the rest of his life terrified of water of any depth, due to having to work hard labour (often being neck-deep seawater), forced to build sea defences for the Japanese war effort, which also meant that he had to live out the remainder of his life with a permanently injured back. On top of all this, he also suffered with nightmares and sweats due to the stress of it all.

Taking all of that into account, it seems that the couple managed to get through the trauma of war and went on to live a long and healthy life, as can be seen is this lovely photo of the couple taken in their later years, below:

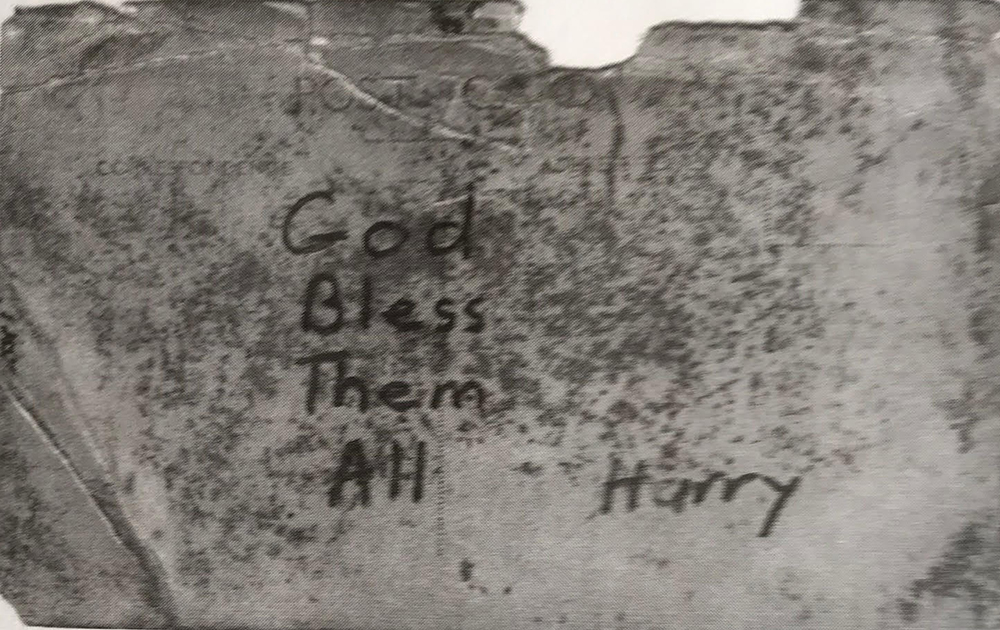

It’s a lovely, warm photograph and you can almost feel the love radiating from those two, broad smiles that have been through a lot in life, and the next set of images show that it was this love for his wife and children that helped Henry (aka Harry) to get through those unimaginably tough times whilst incarcerated in the Changi POW camp. Harry managed to cling on to a small collection of treasured possessions that he had smuggled about his person or regularly buried in the ground at Changi to keep them safe in the form of his leather wallet which contained a couple of photographs and a cutting of paper with the prayer “For those at home” written upon it.

Eternal Father Who alone can keep our loved ones safe at home. We pray to Thee, dear God above, To guide and guard the ones we love. Oh hear our prayer, though we may roam, For all our loved ones left at home. Our thoughts are one, in this great strife, We pray to thee, Who gave us life; Be Thou for ever near and bless Our loved ones through these days of stress. Oh, hear our prayer in speech and mind, For all our loved ones, left behind.

Happy to be back home and with the prospect of long-lasting peace for the foreseeable future Harry and Ivy had two more children after the war named David and Shirley.

It’s amazing what memories and stories you can uncover with a little bit of inquisitiveness and with my question answered about where some of those men were in that Pinder Close VE Part picture, I wondered further.

Now, over the years I’ve built up a friendship with a lady named Gill whose parents had lived in my own home here on the Drayton Estate, Mile Cross, and within spitting distance of Pinder Close, from the 1950’s up until the late 1980’s. She is also a childhood friend of Shirley, mentioned above. A few years back and after a chance encounter on social media, Gill had asked me if she could visit the home in which she had grown up in, and of course I had happily obliged. What made it even more lovely was that she brought with her a bundle of photographs of my house taken throughout those decades, which of course I really loved to see. One – well quite a few- of those pictures was of her father, a man named Albert, who in a few of these lovely photographs could be seen sat in what is/was obviously his space, in the corner of his/my/our living room, and I can still see him sat there now (in my mind), a comforting piece of the history of the house, burnt forever into my consciousness.

When I just typed “my house” it suddenly dawned on me that this collection of bricks, plaster and paint will be here long after I’ve gone, and I too will be a mere memory amongst these walls. Looking at Albert, I noticed that he seemed to be about the right age to have seen a piece of World War Two, so I sent over a message to Gill, his daughter, to see if he had seen any action during the second World War, and sure enough he had. I’ll leave the next part to Gill:

My dad was in the Army. He served in Africa, survived Dunkirk and was captured in Italy and spent the rest of the war in Stalag XVIII Wolsberg, Austria. I have a fair bit of info on this. A few years ago Keith and I (Gill’s brother) went to Austria and found the farm my Dad was sent to work on and found it was still owned by the same family! After the war he was mainly a builders labourer but he also worked at May and Bakers for a few years. My mum worked at the Swan Laundry before the war. She asked for the day off to marry my dad in Nov 1939, was refused, she took the day off anyway and was sacked when she turned up for work the next day. She then went to another laundry but eventually went back to the Swan and all was forgiven. Later in life she worked at Edwards and Holmes shoe factory (Which explains all the shoe lasts I’ve found in the garden).

He was a member of the crew of “HMS Norfolk”…. the Army’s very own ship of the desert. Made up exclusively of Norwich volunteers from 258 battery of the Norfolk Yeomanry who went into action against Rommel’s panzers on board a two-pounder portee (a mobile artillery piece, normally mounted to a flatbed truck) with a giant swede painted on the door. One of the crew of “HMS Norfolk was Roger Perry”, chairman of the local branch of the Yeomanry’s old comrades association. And, as he recalled, this was one ship where the danger of being left high and dry was more often than not a distinct possibility. “You used to get six men on that truck and seven gallons of water a day – to drink, shave, wash and top up the radiator. And if you had a thirsty truck that simply meant you didn’t have much to drink”! The crew member was a sergeant, Sid Spalding and the other members were George Chapman, Don Roe, and Albert Harrison. “We all stuck together, and we all survived the war”, said Roger. His own active role in 258 battery was brought to a premature end when the jeep he was driving was blown up by two mines. And his wounds were such that while his pals went on to Italy and Normandy, Roger was still serving in a Cairo base depot on VE Day.

Back to dad, and a journey we went on to find out more about his past… It all started some time ago when I began researching my family tree. I entered details of my immediate family on a well known family research website and quickly realised how little I knew about my father’s time as a prisoner of war in WW2. Like many others my father, Albert Harrison, never talked about the war and my two brothers, Keith and Andrew, and I knew only that he was a POW in Austria, and that he had worked on a farm. There were five photographs in a family album but any questions to our mother regarding their origin were met with, ‘They’re the people your Dad was with during the war.’

After examining a few related documents and talking to other family members I was able to piece together that Albert was a gunner with the Royal Artillery 65th Anti-tank Regiment (Norfolk Yeomanry) in 1939, he fought in France before evacuation through Dunkirk, then North Africa, was captured in the Middle East (Egypt) on 28th June 1942, taken to Italian Campo 57 and later to a prison camp in Wolfsberg, Austria. A simple Google search led me to a wonderful website http://www.stalag18a.org.uk where I found Albert listed, confirmed by his prisoner of war number which I had found on documentation.

I exchanged several emails with the website owner, Ian Brown, who told me to look on all paperwork for a Work Party number which would identify how and where my father had spent the rest of the war. Apparently Stalag18a was only a holding camp – all POWs were sent out to work, some on farms and the less lucky ones in quarries, factories and railways.

Unable to produce the required number I decided to send an email to an Austrian newspaper Kleine Zeitung. I was very lucky to find that my enquiry coincided with the opening of an Exhibition about Stalag18a at the Lavanthaus Museum in Wolfsberg, Carinthia, which was a joint effort by the museum owner, Igor Puck and Ian Brown. The newspaper agreed to feature an article including our 5 photographs, and Igor kindly offered to display the article as part of the Exhibition in the hope that someone would recognise the farm or some of the people in the photographs. Unfortunately their efforts were unrewarded except for a very nice letter I received from an Austrian lady called Steffi who had lived near the POW camp during the war, married an Englishman, lived in Norwich for 50 years and is now back in Wolfsberg. Then, out of the blue, the Work Camp number was discovered on the back of a photograph sent to my father at, Stalag18a, by his sister in 1943. Ian Brown was immediately able to confirm that Albert was sent to work on a farm at Dietersdorf, near Zwaring Pöls, in Styria which is about 50km from Wolfsberg and would explain why there was no response to the display at the Exhibition!

So, armed with this new information and encouraged by Ian and members of my family I decided to take a trip to Austria to see if the farm could be located and set off on 4th June with my husband, Roy, my brother Keith and his partner Sue. We took with us the 5 photographs and some questions translated into German on Google which we intended to take to all the farms in the area of Dietersdorf and Zwaring Pöls.

On the first day we travelled to Wolfsberg, to visit the Stalag18a Exhibition which is beautifully presented, emotion ripping, thought provoking and an amazing insight into the world of POWs at Stalag 18a. We all agreed it was well worth the journey to Austria for that alone. The newspaper article about my search for my father was no longer on display but Daniel, the young man who greeted our arrival, had been involved with it, was very pleased to see us, and made us very welcome. He was very encouraging when we told him of our plans to search for the farm and very kindly rewrote our questions in correct German. We then tried to visit Steffi but found no-one at home so we thought we’d head for Dietersdorf / Zwaring Pöls to have a look round and get a head start on our plans to begin our search for the farm the following day We arrived at the adjoined small villages with lots of houses and farms around us. Picking on a farm that looked a possibility, Roy went to the door and was greeted by a very old man who read our questions and examined the photos but spoke no English and judging by his lack of gesture & body language he obviously knew nothing. We then decided to wait until the following day before exploring any further and spent the evening preparing ourselves for a long day tomorrow and possibly a whole lot of similar disappointments. On the second day we decided to head for a cafe/bar, spotted in the village the previous afternoon, as a starting point, we parked the car, then found the cafe closed. Not a good start but just round the corner we spotted another cafe/bar and inside sat two men having a drink. Asked if they spoke English one of them, Josef, a man of about 75, said yes so we got out the photographs and questions once again and he was immediately interested.

After lots of discussion and questions Josef asked if he could take the photographs, said he’d be back in 2 hours and set off round the village on a bicycle determined and confident that he would find our farm for us.

Less than an hour later, passing our time walking around the village, we spotted him riding hell for leather towards us. He stopped by the kerb, shook his head sadly, and said ‘No, I could not find any of these people in your photographs, they are all dead!’ I was just thinking ‘Well of course they’ll be dead, we weren’t expecting otherwise’ when he thrust a piece of paper with a name and telephone number in front of us and said with a triumphant grin ‘But I have found the farmer’s son!’ Wow! I kissed him on the cheek then Keith & I cried with joy there in the street. An amazing moment. Josef then told us we would have to wait until tomorrow to visit the farm and meet the farmer’s son, Karl Taucher. It was arranged that we would give Josef a call next morning at 10am to arrange a time to meet him at the cafe/bar. On the 3rd day and after a restless night, at 10am on the dot, we gave Josef a call. He told us to come straight to the cafe/bar but warned that we would not visit the farm until 3pm. We arrived to find Josef and two companions, neither of whom spoke English, ready and waiting to pick up the story where it had been left the day before. Out came the photographs to be scrutinised and discussed all over again. Another man arrived to join the party and we were immediately introduced to Anton who turned out to be another of the farmer’s sons! He was shown the photographs and identified not only his parents, the farmer and his wife, but was surprised to also see a photograph of himself. After much discussion, interpreted by a very patient Josef, we decided to leave the men to their beer, find ourselves some lunch, and meet up with Josef at 3pm to visit the farm. All went according to plan and we arrived at 20 acre Schneider Bauernhof (Farm) to be welcomed most warmly by Karl & his wife Christina. Anton and his son Martin arrived soon after and we all sat around a large table in the kitchen, everyone talking at once and poor Josef’s interpreting skills being stretched to the limit. Drinks and delicious homemade apricot jam doughnuts served by Christina were gratefully received even though we had already had lunch. We soon discovered that Karl was only 4/5 years old when Albert was at the farm and Anton wasn’t born until after the war. They have another older brother, Franz (b1938), a priest in Graz, and a sister who has since passed away. Memories were sketchy but it was obvious that much of what the two brothers could tell us came from family conversations over the years. Karl remembered sometimes being left in Albert’s care and that after the war the family talked about him often. He was also adamant that when Albert finally left the farm the family made sure he had the address and urged him to keep in touch. I was pleased to hear that because I have always had a vague memory that there was an unsuccessful attempt by my parents to make contact sometime in the 1960s. We heard that Franz had ginger hair and dad used to pull his leg, telling him he should stay indoors because he would be easily spotted by the bomber planes. We liked this as it indicated that perhaps there had been an easy rapport going on, although it was clear that the language barrier would have been ever present. We were surprised to hear that although all POWs were part of a ‘work party’ each farm was allotted only one. Also the POWs did not sleep at the farm but had a long walk uphill each evening to a camp, through deep snow and sub-zero temperatures in winter and searing heat in summer. Local unmarried girls were responsible for doing the POWs washing but food was provided by the farm. There was a distinct impression that that the family were fond of Albert for as much as it was allowed. Apparently it was strictly forbidden that the farm owners should show any kindness or favours to the POWs. By this time an hour had flown by but there were still so many questions to ask. None of us had noticed Christina busy clattering away nearby until a feast of breads, cold meats and cheese appeared on the table. Of course it couldn’t be refused so we all had to tuck into this food and find room for it on top of the lunch we’d eaten earlier. An unexpected discovery, made whilst the photographs were being perused, not only surprised us but created another huge discussion. First, we realised that one of our photographs could not possibly have been given to dad by the farmer & his wife before he left the farm in May 1945, as we had always believed, because it shows Karl & Anton as teenage men and in 1945 Karl was 5 years old & Anton hadn’t been born! And then, Karl & Anton told us the farmer’s wife in the wedding photograph wasn’t their mother but their father’s second wife who didn’t join the family until after their mother had died some years after the War! Anton suddenly announced that he remembered a letter arriving from England in the 1960s. We all agreed it was strange that the event had not been mentioned by either our parents or theirs. In the end we had to draw the only possible conclusion that probably my father’s attempt to make contact hadn’t been unsuccessful after all. Perhaps he met someone who spoke German who helped him to write a letter to the farm and received a reply along with the 5 photographs. One of the photographs showed a building which had been part of the farmhouse but was damaged by bombs on 16th October 1944. Albert would have been at the farm at that time. We were shown the cellar where the farmer and his family would have gathered during the raid but we have no idea where Albert would have sheltered because it would not have been allowed for him to be made safe in the cellar along with the family. Appreciating how extremely lucky we had been to meet Josef in the bar, and having been told that Schneider Farm had been only his 3rd port of call, we asked him if he already knew Karl and if he already had some idea which farm he was heading for when he’d set off on his bicycle the day before. He told us he knew the family only by sight but had first gone to a friend who directed him to a 2nd farm who in turn directed him to Karl and then – Bingo! We could not, and still cannot, believe our luck – and to think this all happened on the anniversary of D-Day! Eventually we went outside to take photographs of the farm. Obviously it bears little resemblance to how it would have been 70 years ago but most of the outbuildings are still in place. It was overwhelming to walk on the same ground Albert had worked on, willingly or not we will never be sure. Tears flowed and I found it hard not to cry uncontrollably. Keith was also very emotional and Sue & Roy had a tear in their eye too. Eventually it was time to leave. I think we were all exhausted but happy. We promised to come back next year, probably with our caravans in tow. On the way back, with Josef in the car, we visited the site of the prisoner’s camp at Zettling Kaiserwald, 4km from Zwaring. The buildings have all been renovated and are now a pleasant state-owned housing estate, but you could still get the feel of how it must have been back in 1943. Josef told us prisoners had been set to work building a small railway up the hill but it never got finished. Some prisoners had died in the process and are buried in a nearby field. The following day we went back to the Museum at Wolfsberg to tell them the good news and were also pleased to find Steffi at home and spent and enjoyable hour with this delightful 92year old.

We enjoyed a few more days in Austria before heading home feeling very happy that our trip had been extremely worthwhile and had way exceeded our expectations on every count.

Quite a story, and I’m glad that I asked.

I mentioned at the start of this piece that Garry had family living on both Pinder Road and Pinder Close, and the story had more to tell. Garry’s parents were Gordon and Joyce Todd and Gordon was the son of George and Ethel Todd (George’s previous wife had sadly passed away at a young age). A young Gordon was called up for National Service in the RAF Regiment in early 1946, the last of the seven brothers to serve in the forces. Along with their two daughters this was quite a brood! A history of serving in the forces appears to be strong here on The Drayton Estate it seems. Gordon met his wife to be Joyce just around the corner from here at Valpy Avenue whilst he was on home leave from the services, when one day she had asked him if he would give her a ‘crossie’ (a ride on the crossbar of his bike). This was a cycle ride that lead to 66 years of marriage.

Gordon and Joyce Todd didn’t go far, and in 1958 moved just across the other side of Drayton Road and into one of the slightly newer homes at Shorncliffe Avenue, where they had two Children named Garry and Dawn. After leaving the RAF Gordon found work as a professional driver, first as a Heavy Goods Vehicle driver and then as a Taxi driver before hanging up his keys and retiring at 72.

Next to fly the nest was a young Garry when he moved out Shorncliffe Avenue in March 1973 after marrying Arlene Kelly who used to live a little bit further down Drayton Road at Stone Road with her four siblings. Along with all these wonderful photographs of Mile Cross Garry has an abundance of fond memories of growing up here in Mile Cross, from walking down to the Drayton Estate to see his grandparents, going to the nearby Dowson School as well as fond memories of the countryside on his doorstep and the great panoramic view of the city he had from the bedroom window of his Shorncliffe Road home, a view still enjoyed by a lot of families inhabiting these homes situated on the elevated valley edge along this part of the estate.

Gordon, Joyce and Dawn left Mile Cross to West Earlham a few months after Garry moved out where they happily lived out their remaining years. Joyce died suddenly on Boxing Day 2017 aged 86. Gordon died in March 2022, aged 94.

It wasn’t all rose-tinted memories from Garry and he recalled with a wince the harsh school punishments dished out if you were to misbehave at school here. Punishment at the Dowson infants would be to simply be shouted at, but the Dowson Juniors the punishments became a lot more serious, and were regularly beaten with a size 13 plimsole, usually by the headmaster, Albert Ireland. When the children got a little older, the boys would progress up the road to the Norman School where they were also upgraded to the cane, a punishment regularly dished out by the Norman Boys headmaster, Reginald (Reggie) Mace.

I’m glad to say that when I went to Mile Cross Middle the days of violent corporal punishment were long gone, and the worst punishment I recall was being made to stand in the corridor all day by Mr Bremner, and even then I thought that this was too harsh and decided that going AWOL from school for an entire day would be a wise decision. I remember hiding in a stairwell of one of the flats opposite the school on Vale Green and watching the ensuing carnage unfold from the window. It was funny at first, but when I witnessed the police arriving at the school along with my parents from my lofty viewpoint, it soon dawned on me how much trouble I’d created! I finally emerged from my hiding spot at about tea time. Not that I got any tea that night! Garry also recalled that this corporal punishment rarely worked as a deterrent anyway, and that it didn’t stop the boys going back for more.

As a lad growing up on the estate in the 1960’s there was plenty to do and Garry remembers the great days he had with The Aylsham Road Detachment of the Army Cadet Force a thriving Detachment run by John Baldry and Stan Limmer. The detachment was made up entirely of boys from Mile Cross and the Woodcock Road area (Catton). The 25th Norwich cub pack was also thriving and run mainly by Arkela Mrs Softly.

During our chat, Garry asked me if I watched “Who do you think you are”? Not really, but I have seen a couple of episodes. It’s obvious to me they research this stuff in reverse so that they’re guaranteed an interesting story and ‘celebrities’ don’t really interest me. We agreed that the programme would probably be infinitely more interesting if the researchers stood somewhere like Gentleman’s Walk and stopped people at random. The people stopped would most likely have equally fascinating stories, and there’s often extraordinary hiding in the shadows of perceived ordinary, as this piece has illustrated rather well.

Just like the war stories that seemed abundant in my corner of the estate, the school stories were plentiful too, and I go back now to Gill, who lived in my house and whose Dad was also a POW. She also went to the Dowson, just like Garry and just like me a few years later when it was Dowson and Mile Cross, and she also had a brilliant School photograph taken on the playground, this time taken in 1960 and of Miss Churchyard’s Class.

Like the 1950’s picture of the playground shown earlier on in this piece, this lovely image shows the playground but looking the other way, looking towards the Dowson Road side of the school (the Dowson Junior, or Mile Cross Middle when I was there). This image shows the toilets and drinking fountain, mirroring those on the infants side, both demolished before I attended. It also shows what I think I remember to be the music room (taught by Mr Foster for those of you in my age bracket) and you can just about make out three inquisitive children watching the photograph being taken from the window.

It’s wonderful how all these stories connect and that how people’s personal history are all intertwined and in one way or another and it’s a brilliant example of how being inquisitive and asking a few questions can dig up so many lovely memories and images. It’s amazing what you can find by digging into the background noise of it all. I’ll end this piece with a picture I found whilst digging about in the back area of the heritage centre for the Mile Cross 100 research project and it is of Mile Cross Middle School in the 1980’s. When doing what I do by delving into the background of old photographs, scanning the image in detail in Photoshop I started to recognise the faces looking back at me, some of which I haven’t seen in almost 40 years and to my great surprise started to realise that these were my classmates. One of which turned out to be Gill’s son. I’ve said it before and I’ll probably say it again, but even across the expanse of time, this really is a small City. I scanned further, and on the very edge of the image I found a jumper and a haircut that have both since been lost to the sands of times. Yup, I had found myself looking back at me from almost forty years ago. It didn’t half make me smile.

So there you have it, if you love your local history, just do a bit of digging and follow your nose, and if you don’t know where to start, a great starting point is the Heritage Centre or the Record Office, which are both free to use and well worth your time. If you do have anything Mile Cross related that you’d like to share, no matter how insignificant you may believe it to be – I guarantee there’s a story or two hiding in amongst the ordinary – please get in touch. It’s too late for the book, which will be out soon, but there’s still time to have it added to the Mile Cross 100 website if you’re quick. Follow the link below to get in touch or to just explore it (it’s already brilliant), or just send me an email.

100 Years of Mile Cross Website

Thanks once again for reading this stuff, I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I do researching it.

Stu

Another excellent piece of local history, well done!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great bit of story-telling, really enjoyable

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely loved reading and seeing the photos on your article on Pinder Road/ close . My late father’s family lived in Pinder close during the Second World War and up until the early sixties. Thank you

LikeLike

Sorry Stuart but I don’t remember this!! “the worst punishment I recall was being made to stand in the corridor all day by Mr Bremner, and even then I thought that this was too harsh and decided that going AWOL from school foe an entire day would be a wise decision. I remember hiding in a stairwell of one of the flats opposite the school on Vale Green and watching the ensuing carnage unfold from the window. It was funny at first, but when I witnessed the police arriving at the school along with my parents from my lofty viewpoint, it soon dawned on me how much trouble I’d created! I finally emerged from hiding spot at about tea time. Not that I got any tea that night! ” Was it that you were told to stand in the corridor, and after a moment decided to go AWOL? So not all day outside? “stand in the corridor all day” doesn’t sound right, as there would have been breaks, lunch time etc etc.. Feeling guilty – Bert Bremner

LikeLike

That was very interesting. It fired up memories of my own time at Mile Cross.

I was at Dowson Juniors up to 1962. I wasn’t Mrs Churchyard’s favourite pupil, and Mr Ireland wasn’t my favourite headmaster, with his greased back dark hair.The boys toilet block was open to the elements so you got wet if it was raining, as were the drinking fountains.I remember the iron railings that separated the playgrounds, and the fields opposite that were allotments before Vale Green was built. Under these allotments were air-raid shelters but I was never brave enough to investigate. Daily 1/3rd pint bottles of milk were welcome, together with biscuits which we had to purchase, with profits going into the Christmas fund. Short trousers were order of the day, but one very cold day in winter I wore long trousers to school and was chastised for breaking the rules, but after consideration, special dispensation was granted so that I could go to and from school in long trousers for the cold spell but had to change into short trousers as soon as I entered the premises. I don’t particularly recall the classrooms being overly warm in winter or cool in summer.I took part in after school judo classes in the main hall (remembering how cold the judo mat was to bare feet).I also participated in ‘joining the snake’ practice in the playground at lunchtimes….this was a line of us kiddies holding hands with the leader running off and when we were all up to speed they would turn sharply forcing the line to become a whip which got faster and faster with the last person having to hang on for dear life. One such day I was the last of the line, but on my roller skates which saw me speeding across the playground after I couldn’t hang onto the hand of my forerunner, and in desperation to avoid crashing into the verandah/classrooms I tried to brake but fell and broke my left wrist and ended up in the ‘Jenny Lind’hospital being put in plaster.I remember the fenced garden area opposite the school entrance on Valpy Avenue, but was never aware of what or whose it was.Oh, and I remember enjoying dancing in the hall (lots of Scottish reels) with skipping and spinning in tandem (especially when you partnered the prettiest girls). And, school dinners: usually good especially the sweets but on one particular occasion when I was forced to eat every butterbean on my plate, it was touch and go whether the last one would stay down or end up with the teacher wearing it….lucky for her, it stayed down (but in hindsight it would have taught her a lesson it it hadn’t stayed down!)Having passed the ’11-plus’ in 1962 I waved goodbye to the Dowson and headed off to grammar school for the next 5 years.

Picking up on part of your text, I recall the sandy track with grass on both sides that continued opposite Parr Road, over Valpy Avenue. There was a old American car languishing along it, going rusty and had been vandalised. This track turned into a T-junction, going left towards where the Corporation depot was built, and going right, leading to the back of Sloughbottom Park. I spent many happy times rolling down the slopes from the pavilion down to the pitches either side of the tennis courts, and sledging down the same slopes when it snowed. The park keeper had reprimanded me over time, for riding my bicycle around the perimeter paths, and climbing the trees and being a nuisance…..childhood exuberance / happy days.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lovely memories, thank you.

LikeLike